On my birthday last year, one of my favorite songwriters released a new album. "Denis Was a Bird" was in its entirety a journey through the grief that Tom Rosenthal experienced after his father died of Parkinson's Disease in 2019. Throughout the summer, Tom posted teaser videos on social media. I discovered the upcoming album by accident sometime in the predawn hours of June 18, 2021. Tom had premiered a new video just hours earlier, so it showed up near the top of my feed as I scrolled mindlessly through Facebook, straining to feel anything else.

It was our first night in Utah following the most bewildering nine-hour drive of my life, which Beat and I made to be with my family after my father died suddenly in a hiking accident. The trip started the morning of June 17, when we had to crawl behind a cyclist in a bright pink jersey for the entire five-mile descent of Flagstaff Road. This is the only part of the drive of which I have any clear memory, because I (as a passenger) boiled over with road rage so blindingly overwhelming that this experience of losing my shit — more than anything else — has made me fearful of being a vulnerable cyclist on the road. But even vague images of the rest of the drive still haunt me: the slow crawl in summer traffic along I-70, blinking numbly at rest stops in the 103-degree desert, and again boiling over with rage as wildfire smoke choked the air over eastern Utah.

It was after 3 a.m. I hadn't slept. Beat was upstairs and I was sprawled in my mother's unfinished basement, hiding from the heat, hiding from the threat of sunrise, shaking from the monster of pain churning in my gut and wishing I could just violently rip it from my body. No physical pain could be worse than this.

The song, which I suspected would be hurtful to hear but clicked the link anyway, is called "I went to bed and I loved you." The video depicts clips of various people from around the world standing or dancing with portraits of lost loved ones. The lyrics are brilliant and shattering, but a particular line left me sobbing. I shook so hard I thought the monster of pain might be crushed for good. Of course, it was not, but a hint of perspective managed to slice through the devastation.

The line is:

I don't see you as a force above.

You're down here.

Sparks in all of us.

Somewhere in the lost light of every room.

|

| A belated birthday outing at Glacier de Corbassière on Aug. 21, 2021 |

When the album came out on Aug. 20, I purchased the digital version from the Frankfurt airport and listened to it repeatedly while hiking up and down every steep trail I could find out of Verbier, Switzerland. I tend to do this with Tom's music when I'm feeling fragile — Tom Rosenthal's songs essentially got me through the Iditarod in 2018, and again in 2022. The music is just so simple and honest, quirky yet vulnerable, blunt yet hopeful.

Walking up the hill again

To see you

I don't know when I will again

Time feels new.

I never had an opportunity to bring my Dad to the Swiss Alps. We had been planning a summer trip in 2020. I was so excited; I amassed a folder full of trails we could hike, AirBnBs where we could stay, and mountain huts where we could sample local cakes while overlooking glaciers and snow-capped peaks. It would have taken a month to do everything I wanted to do. Then Covid happened, and then time ran out. As August 2021 approached, I wanted to cancel my plans to travel with Beat to Switzerland. I couldn't bear the thought of being in these mountains, walking alone, knowing I'd never be able to share this with Dad. Apathy and inertia, more than anything else, caused me to continue with the trip as planned. Of course I'm glad I did. Hiking in the Swiss Alps was the first time since he left that I felt, really felt, Dad walking beside me.

All the while, I had Tom Rosenthal telling me in every way possible that everything was going to be all right.

It's not a catastrophe It will happen to you and it will happen to me

And the sky won't fall down to the sea

And the joys won't end with you.

Grief has been an interesting journey. The lows can be so low, and yet there are brilliant moments of the purest joy, these streaks of white light through the darkness. I can feel my values shifting along this axis of the light, in ways I don't yet comprehend. It's the same old existential dilemma: If life is a cosmic accident with no inherent purpose, then where do we find meaning? And the answer, obtuse and simplistic as it is, remains: We create our own meaning. But how? The darkness helps sharpen my perspective. Pay attention. What makes the light? This is what matters.

Send me into the long night with all your

Little joys, little joys, little joys, little joys

Little joys, little joys, little joys

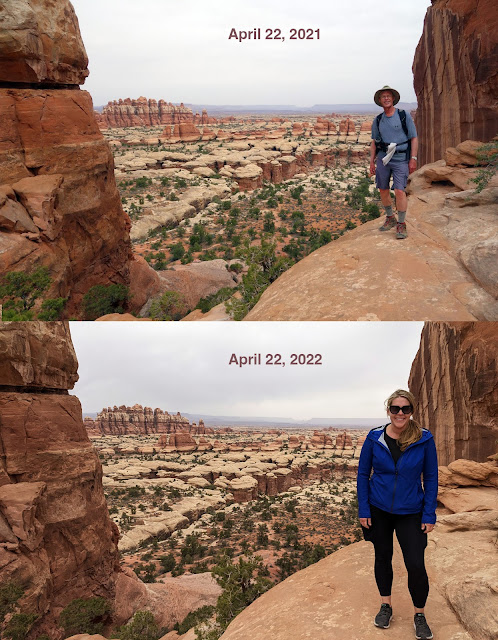

Of the finite

My dad brought so much light to my life, but one important realization of my journey through grief has been this: He still brings light to my life, and always will. All that remains is all that matters: The countless little joys that I can reach out to grasp any time I choose, or at least any time I can muster the strength to turn my gaze from the darkness. One of these little joys is Canyonlands National Park, Dad's Heaven on Earth. If he could choose, he would spend eternity in the midst of these sculpted sandstone spires, and told Beat and me as much when we visited in April 2021. Dad had three specific spots where he wanted his ashes spread after he died, and two of them were in the Needles District of Canyonlands. As we trekked along his favorite trails, Dad deliberately pointed them out with enough emphasis that both Beat and I both remembered the exact spots. I took photos to document the locations. We joked that he'd have to train his grandkids because Beat and I would be too old and decrepit to make the journey by the time he finally went. After the trip, I posted this photo and caption on my Instagram:

|

| April 23, 2021. |

"Over the weekend, Beat and I joined my 68-year-old father on his annual journey into Canyonlands Needles District, where he revisits some of his favorite places in the world every year. Here, my dad is overlooking a spot where he would like his ashes spread someday — overlooking "The Sentinel." I told my dad that he'll probably outlast that rock formation."

|

| Dad and my sister Sara standing at the exact same overlook, exactly one year apart. The dates and picture poses were unintentional — this is just how it worked out. |

I broached the Canyonlands issue within hours of arriving at home on June 17. I wasn't sure whether Dad and Mom had discussed his final wishes. In their religion, cremation was once verboten or at least heavily discouraged. It's still outside the norm — most members of the LDS faith are buried in cemeteries next to their parents and other relatives, usually with space reserved for a spouse. Often the name and birth date of the still-living spouse are carved into a shared headstone, which I always thought was a bit creepy. I already understood that my mom wished for a traditional burial. And I didn't know whether Dad had ever discussed alternatives with her. He hadn't shared much with me about his desire to be cremated before he rather presciently brought it up in April 2021.

I was nervous about approaching Mom. He'd discussed it with her, but only in passing, and there was nothing about burial in his will. (Humorously, what he did include in his will were the three classic rock songs he wished to have played after his funeral, as well as the longtime friend who he wanted to sing during the service — "if he's still alive.") I was ready to fight for what I strongly believed to be Dad's final wishes, but was also willing to concede if Mom was going to be deeply upset — after all, she's the one still living; what matters to her is what matters. Mom surprised me by agreeing to cremation without hesitation. My sisters also were strongly on board. We made the arrangements and planned for a closed-casket service with a decoy casket and a strategy to discretely handle prying questions from relatives. Then we started making plans for our private family service in Canyonlands.

"It has to be April," I said. "That was his time."

|

| With my sisters and mom in April 2022. |

We booked dates in late April, and I spent far too much time and energy fretting about how it would work out — hopefully the weather wouldn't be too harrowing, and hopefully Mom could handle the long hikes, and hopefully I wouldn't panic at that weird exposed spot on the Peekaboo Trail like I did in 2021. As it turned out, I ended up with the biggest issue to overcome. Back in January, I fell down my stairs at home and broke the pinkie toe on my right foot. I'm not sure this was the exact nature of my injury, but it was incredibly painful and surprisingly debilitating and yet "just a toe." I continued with my Iditarod training and raced the difficult 350 miles with long miles of pushing my bike in late February. I think as a consequence, the appendage never fully healed. Then, two days before we were set to leave for Utah, I fell down my stairs again, and again jammed the exact same toe that again turned purple and swelled like a rotten grape. I panic-texted photos to my physician friend and physical therapist and again got the "it's just a toe" advice. So I packed a supportive, 20-year-old pair of Vibram-soled leather hiking boots and hoped for the best.

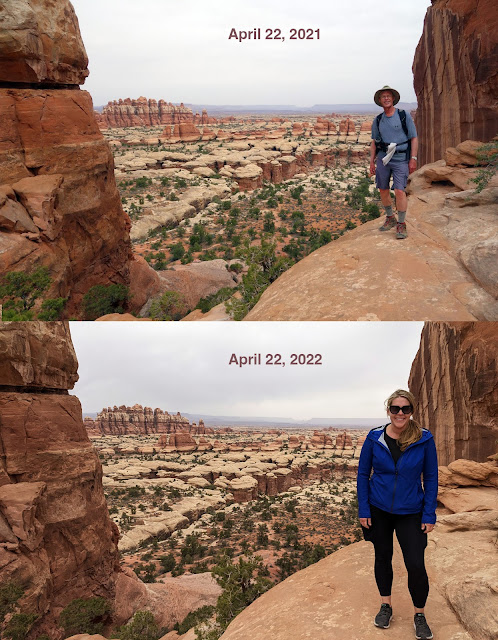

It is strange to be in a fair amount of physical pain during an emotionally cathartic experience. At times I could put it out of my mind, but for long stretches, I could not. My toe throbbed and sent continuous signals to my brain to stop walking already. For that reason, I couldn't quite slip into the flow that I rely on to find peace in my hikes. It took focus to remember what I was doing and appreciate where I was. I wondered if my mom was feeling something similar. She engaged in daily 3- and 5-mile walks to prepare for these hikes, but it had been a while since she hiked technical trails with so many ups and downs. The forecast called for one day with a high likelihood of thunderstorms, and a second slated to be cold and breezy but dry. So I flipped our original plan around to start with Chesler Park — the less technical trail, and end on Peekaboo. Because of this, we ended up on each trail exactly one year to the date of my Dad's final hikes here. It was unintentional, but fitting.

|

| April 22, 2021 in Chesler Park. |

In 2021, Dad, Beat and I descended from a bench onto this sandy ribbon of singletrack when Dad first described his wishes to have one of his final resting places be among these sandstone spires. He stopped briefly to turn to me, spread his arms and made a sweeping motion with his hands.

"Anywhere in here," he said.

"Anywhere?" I asked, looking around for a tangible landmark. It was all vast open space, brush and cryptobiotic soil.

"Anywhere," he confirmed as Beat pointed toward a distant boulder.

"Maybe over there?"

"Anywhere," Dad repeated. I took the above photo, because this was the spot. It had to be here.

|

April 22, 2022 in Chesler Park.

|

In the 2021 photo, you can see hints of a sandy wash lined with juniper trees. We chose this wash for his eternity in Chesler Park — ashes to ashes, dust to dust. It was 4.5 miles from the nearest trailhead, a little farther than I'd guessed, but a beautiful and quiet stroll amid the hoodoos. Strong weather was already moving in when we stood in a half-circle facing these formations. I didn't know what to do or say. I'd never done anything like this before and had only experienced a similar service once before when my friend Raj spread some of his father's ashes at White Pine Lake in July 2021. I'll admit that the act was awkward but gratifying. I whispered goodbye as the gusting spring winds swept Dad away.

Then the rain arrived — hard, cold, and persistent. Red water gushed down previously dry channels. I carried several extra jackets but wasn't quite as prepared as I should have been for a typical April deluge in the desert. Strong gusts buffeted us as we contoured sandstone benches. I was a little nervous that we wouldn't be able to ward off hypothermia. Luckily we dropped into a canyon, where we had to wade through baby flash floods, but at least we were protected from the wind.

It was quite the adventure. Mom mentioned several times that Dad wouldn't choose such a wet day for a hike, but this wasn't exactly true. While he was talented at optimizing for ideal conditions, he wouldn't let a sudden shift in the weather stop him. In 2018, we hiked the Peekaboo Trail in a full April snowstorm as powder accumulated on the rock. This day, because it was so much wetter, felt even colder. Lisa didn't complain until she fully lost feeling in both hands (I offered my own pair of soaked gloves, which didn't help.) Beat, dressed in typical running garb, opted to run ahead. Sara and Mom didn't complain at all. I like to think Dad would have been proud.

There's a lot of you in this light

Nimble in your footstep, dashing out of sight

Every corner is written by you.

I was nervous about taking my family on the Peekaboo Trail, only because it's hard for me — all of that off-camber sandstone, scrambles in and out of drainages, and brief exposure. As is my way, I overthought the entire thing and proposed an alternative approach along Salt Creek Wash — a boring sand slog that truly only Jill could love, or at least tolerate. They rejected my proposal soundly, and I tried hard not to let anxiety get the better of me.

|

| Beat plays peekaboo on the Peekaboo Trail. |

As forecast, the day brought cold wind but blue skies. The Peekaboo Trail is a real crowd-pleaser with fun playground-like terrain and dynamic vistas of redrock skyscrapers and canyons bursting with spring green. My sisters were in awe, which was fun to observe. Mom struggled more on this day, but she never made a peep about it, even after we admonished her to sit down and finally eat something. The snacks, in honor of Dad, were pita bread smeared with Nutella, Maui sweet onion chips, and a trail mix that was exactly half peanuts, half regular M&Ms ... why Dad didn't just eat Peanut M&Ms, I never understood, and now I'll never have a chance to ask.

Despite everything going well, anxiety had scrambled my brain somewhat. Somehow, I convinced myself that the rock formation we were contouring around wasn't "The Sentinel."

"It's larger than that," I insisted. "And it's farther away." As we rose to the upper bench, I spotted a nearby butte with rock debris littered around the base. I let myself believe, maybe for longer than I should admit, that the Sentinel had collapsed.

"Wouldn't it be wild if Dad did outlast the Sentinel?" I babbled as Beat shook his head. This runaway fantasy was fun while it lasted, but eventually, I had seen the Sentinel from enough aspects to leave no room for doubt. The formation still stood.

The place Dad had pointed out last year wasn't exactly in the shadow of the Sentinel, but rather the highest point on the route with a panoramic view that swept across much of Canyonlands. We each took a turn standing at the edge to share a few sentences of gratitude and release a handful of ash to the gusting wind. The ashes, shimmering in the sunlight, swirled through the breeze for long seconds, traveling out of sight before they could settle. The intent was Leave No Trace, but the effect was mesmerizing in its beauty. Sparkle and fade. Dust to dust. The awe of impermanence. Now, Dad can rest all across this valley, and all under the watchful gaze of the Sentinel. Of course, even the Sentinel can't last forever.

I thought that life would be a lot without you here

It's alright

Now that you're kind of еverything and everywhеre

In low light.

No other hikers passed this spot the entire time we were there, nearly an hour, unheard of for a sunny Saturday afternoon in April. But so it was. We enjoyed the peace and silence of Heaven on Earth. I quietly thanked Dad for giving me an excuse to return to this place at every opportunity possible. It's just so meaningful compared to a manicured cemetery crowded with hundreds of strangers.

I'm not sure where I want my body to go when I die. To be entirely honest, I don't really care. Perhaps it could be mulched somehow and used to fertilize a tree, although that may be overly complicated or outlawed. With any luck, I'll be very old and there won't be many left to mourn my passing, which is just fine with me — although also to be entirely honest, my greatest fear is that I'll outlive all of the people I love. In my wildest fantasies, I'm under an avalanche of snow or the bottom of a ravine and left there to be devoured by the elements, although I realize this isn't fair to the living. Cremation is probably the most practical solution, and perhaps there will be someone out there willing to spread my ashes on Rainy Pass in Alaska. Or — even more appropriate — Lone Peak.

Lone Peak is the next and final step in this particular journey. It was the third spot my Dad expressed a desire in having his ashes spread, and it's the most difficult to reach. I've been to this summit in the Wasatch Mountains at least six times, but only once without my dad. It was 2010 when I decided to climb up there and release torn-up pieces of paper on which I had written memories of my dad's Dad. Grandpa Homer died on Sept. 4 of that year. The climb ended up being a harrowing experience — I hadn't before realized how safe I felt with my father until I was clinging to a rock slab with my butt hanging over hundreds of feet of empty space on the summit ridge. But later this summer, perhaps on Sept. 4, I intend to climb Lone Peak with my Dad one more time. I believe he'll provide the peace I need to surmount my anxiety and finish the journey.

Nothing to save, no more weather delays

Nothing to lose, no more troubles for you

I can still see you running around

And if it stays in my mind, then it's not gone.